Colonel George Davenport, founder of Davenport, Iowa, and first white settler in the area, led a family life that today would be fodder for the tabloids. Regardless, as a sutler for the U.S. Army, fur trader, and representative of Indians in negotiations with the U.S. government, he was well respected until his life ended tragically. In this podcast, we chat about the Colonel Davenport house on the Rock Island Arsenal in the Quad Cities and Colonel Davenport’s fascinating life.

Listen to the Colonel Davenport House podcast:

Thank you to Visit Quad Cities for hosting us in the area.

This article may contain affiliate links, though which we may receive a small commission. Read our Privacy Policy for more information on affiliate links.

[expand title=”Click here to read the transcript”]

Skip: Welcome to Midwest Wanderer. I’m Skip.

Connie: I’m Connie.

Skip: Today’s topic is the Colonel Davenport House, located on the Rock Island Arsenal in the Quad Cities.

Connie: We toured the house during our visit to the Quad Cities.

Who was Colonel Davenport?

Skip: Connie, do you want to talk a little bit about who Colonel Davenport was?

Connie: Sure. George Davenport was actually born in England and ended up in the United States by accident—literally. He was a sailor on a merchant vessel, and in the year 1804 they had delivered cargo to New York. They were on their way back to Liverpool with another load of cargo when one of the crew members was knocked overboard. George jumped in to save him and in the process broke his leg. The break was so bad that he ended up in the hospital for two months. And of course, the ship couldn’t wait for him, so they took off without him, planning to pick him up on another trip.

Well, after the two months in the hospital, George’s leg still wasn’t a hundred percent, so the doctor sent him to the country to convalesce, and he eventually ended up in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. And then he was recruited into the Army. I guess by that time he was considered an American, America was his adopted home.

Skip: George spent ten years in the Army, mostly fighting against Indians.

Connie: He was discharged then, but the Army wasn’t quite finished with him.

George Davenport Becomes a Sutler

Skip: No. They actually hired him as a sutler.

Connie: Sutler was a new term to me this year. I learned that a sutler was a civilian who was hired to supply provisions to the military.

Skip: Right. And George Davenport accompanied a Colonel Lawrence, who was in command of the Eighth Regiment United States Infantry. They headed up the Mississippi River looking for a location to build a fort. They ended up on Rock Island, which today is still a military operation, the Rock Island Arsenal.

Connie: Rock Island is the largest island in the Mississippi River. It’s between Iowa and Illinois.

Skip: So that’s where they built the fort, and that’s where George Davenport settled.

Connie: Yes, George was the first white settler there. That was considered the frontier back then, in 1816. And He lived there the rest of his life.

Skip: Yes. He first built a log cabin. I was surprised at how huge the timbers were.

Connie: Yeah, they were really big. And the reason we know that is because, although a house was built around the log cabin walls in 1833, when they renovated the house, they left part of it open, covered with Plexiglas, I think it is, instead of plaster, so you can see what it was like.

We’re jumping ahead, though.

Skip: So George Davenport—he wasn’t yet a colonel—set up business as the sutler.

Connie: He raised cattle and hogs on the island, planted an orchard and grew vegetables. And he sold all of those things to the Army.

Colonel Davenport the Entrepreneur

Skip: But Davenport was quite the entrepreneur. He didn’t just sell to the Army. European settlers were starting to move west, and they also needed supplies. So he opened a store in what is now Rock Island—the city on the Illinois side of the river. And then he started trading with the Indians as well.

Connie: He had developed a good relationship with the Indians. He became a fur trader, working with the American Fur Company. That was the company owned by John Jacob Aster.

Skip: The Indians would bring in the furs, and Davenport had a list of prices. For a prime quality beaver, he would pay two dollars. For a bear, he would pay two to three dollars.

Connie: It seemed surprising that a little beaver would be worth as much as a bear. A bear is so much larger.

Skip: Beaver fur was used for hats.

Connie: Right. Beaver fur was pressed into felt for the hats that were so popular then. Supply and demand.

Skip: And a male deer was worth one dollar.

Connie: A buck for a buck. That’s actually where the term “buck” meaning “dollar” came from.

So he traded and sold everything from axes and blankets, even horses, with the Indians and settlers. And for the settlers, many of them were very poor, so George often gave them provisions until they could raise a crop.

George Davenport Becomes a Colonel

So we mentioned before that George Davenport didn’t have the colonel designation yet. Let’s talk about where that came from.

Skip: That came during the 1832 Black Hawk War. Illinois Governor John Reynolds appointed him quarter-master general with the commission of colonel. That war started when a 65-year-old Sauk warrior named Black Hawk led about a thousand Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo Indians across the river back into Illinois to reclaim land that had been surrendered to the U.S. back in 1804. Black Hawk claimed they never sold the land.

Davenport, along with Antoine Le Claire, worked with the militia and helped bring about the truce and helped finalize the treaty. In gratitude for his services, the Army paid Davenport $40,000.

Connie: Wow, that’s a lot of money. I have no idea how much that would be in today’s dollars. I tried to find out, but the calculator only went as far back as 1914. $40,000 in 1914 in today’s dollars would be over a million dollars. And we’re talking about over 70 years earlier.

But some of that money was to repay him for what the Indians owned him. George would give the Indians credit. Say they needed a new trap. George would give it to them on credit at the beginning of the hunting season, and they would pay him in furs later. Well, now that the Indians couldn’t hunt there anymore, they couldn’t pay George back. So some of that money George got from the Army was because of that credit that couldn’t be repaid.

The Colonel Davenport House

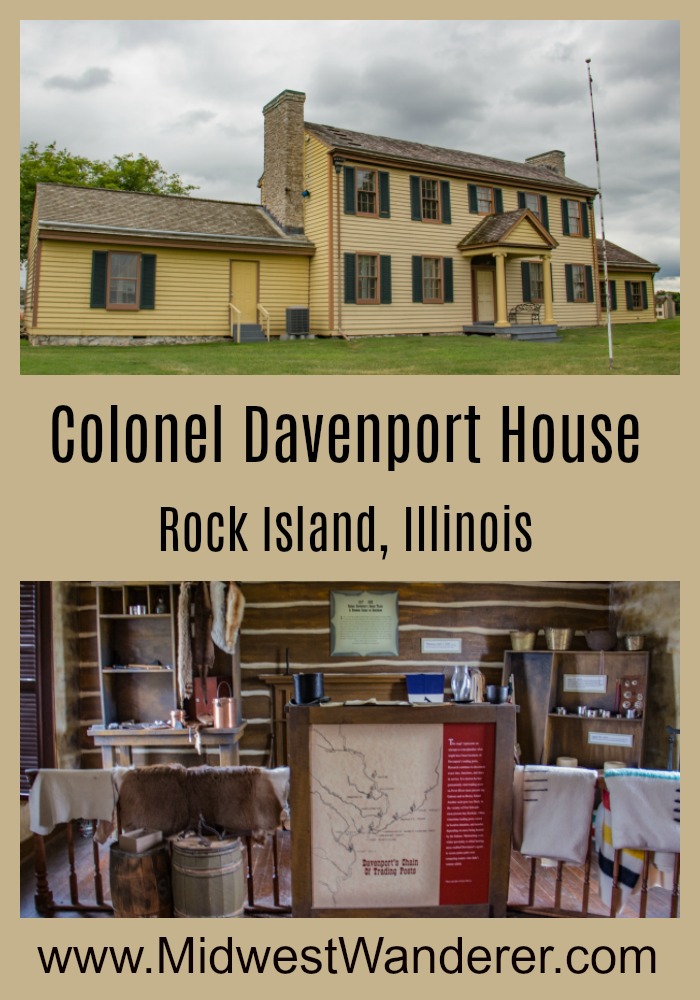

Skip: And the following year, in 1833, he built the clapboard two-story house around the cabin and added a wing on each side.

Connie: Imagine that. And he furnished it very elegantly, with Empire style furniture that was so popular in Europe at the time. The furniture actually was shipped over from Europe. It was the furniture to have in the 1830’s and ‘40s in well-to-do American households.

The house today has been furnished with period furniture similar to what George and his family owned. There is only one piece that is believed to have belonged to the Davenport family. That piece was given to the Colonel Davenport Historical Foundation, the organization that maintains the house and runs the tours. According to family lore, the table was given to a woman who worked for the Davenports when she was married and left their employment. It can’t be proven; they can only assume it’s true.

Colonel Davenport’s Family Life

And then there’s the whole family issue.

Skip: I’ll let you talk about that.

Connie: Well, a lot of it is a guess. But on paper George was married to Margaret Bowling Lewis, a widow 14 years his senior. Margaret had a daughter from her first marriage. Her name was Susan Lewis. Now, the mother of George’s two sons was Susan (the step-daughter), not Margaret (the wife). The guess is that Susan was actually his wife, but in order to bring the mother-in-law to the United States, he said he was married to Margaret, not Susan. And rumor has it that George had more children, by several different women. Only a daughter was acknowledged.

Skip: Regardless, Colonel Davenport was well respected in the community, and he was elected one of the first county commissioners when the county was organized. He, with others, also purchased a claim on the Iowa side of the river and laid out a town.

Connie: And that town was named after him, today’s Davenport, Iowa. And then he died in a tragic incident.

Skip: Tell what happened.

Colonel Davenport and the Bandits

Connie: On the 4th of July in 1845 there was a big picnic in Rock Island. The entire family was planning to go, but George decided to stay home. He had heard that there were bandits in the area, and he wanted to stay home to protect his home.

Sure enough the bandits showed up. They had heard that George had a large sum of money in a safe. It was money that was to go to the railroad. It’s true that he had had the money, but it was already sent to the railroad. But the bandits didn’t believe him. They shot George in the leg, dragged him upstairs, and beat him trying to find out where the money was. George did end up giving the safe combination to the bandits, and they took some banknotes that were in there, as well as George’s gold watch and a few other things.

Once the bandits left, George managed to make his way to the window. A fisherman passing by heard him and summoned the doctor and George’s family. But George had lost too much blood, and he passed away.

Skip: But they caught the bandits.

Connie: Yes. Before he died, George was able to give a detailed description of the bandits. I believe there were four or five of them. George also knew the numbers on the banknotes. They offered a $1500 reward for the bandits’ capture. They did capture them, and the bandits were hanged. So a tragic ending.

Skip: It sure was.

Colonel Davenport House Tour Details

So let’s talk about touring the house.

Connie: Right. We mentioned that the house was built around the original log cabin, and then two wings were added. There had also been a detached kitchen. But the house was in shambles before they began restoring it. It sat vacant from 1867 until 1907, so about 40 years. George Davenport’s granddaughters and a group called the Old Settlers and Pioneers were able to save the main portion of the house, but the wings were too far gone. But then over the years more restoration was done and the wings reconstructed. So only the detached kitchen wasn’t added back to the house.

Tours of the house are offered from May through October, Wednesday through Saturday from noon until 4 p.m. Admission is only $6 for adults, $4 for seniors age 65 and over, and free for children 12 and under and military.

Skip: And because it’s on an active military installation, visitors age 18 and over are required to get a visitor pass. You enter the arsenal through the Moline, Illinois, gate and then stop at the Visitor Control Center. You’ll need a government-issued ID, like a driver’s license or passport, and the last four digits of your Social Security number. Once you get the visitor’s pass, it’s good for one year.

Well, that ends this episode of the podcast. Thank you to Visit Quad Cities for hosting us during our time there. And thank you for listening. Be sure to check our photos of the Colonel Davenport House on our website, https://www.midwestwanderer.com.

Safe travels.

Connie: And happy travels.

[/expand]

Accommodations

During our visit to the Quad Cities, we stayed at the Rhythm City Casino Resort. Check rates and review on TripAdvisor

Pin It!