Driving onto the Village of Grand Traverse Commons grounds on a sunny day should have been a tranquil experience. Massive old shade trees dappled shade across the expansive green lawns. Beyond the front lawn stood towering three-story 1880s Victorian-Italianate buildings. However, instead of tranquility, I felt a bit of eeriness. Had I not been aware that the 500 acre property was once a mental health asylum, maybe the eerie feeling wouldn’t have existed. Read more

Laurent House, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Little Gem: Rockford, Illinois

Frank Lloyd Wright referred to it as his “little gem,” the small house in Rockford he designed for Ken and Phyllis Laurent, the only house he designed for a person with a disability. The house, completely rehabbed by the Laurent House Foundation, opened to the public for tours in 2014. Jerry Heinzeroth, Foundation President, was kind enough to meet Skip and me at the Laurent House this summer for a tour of the home and to share the home’s history with us.

Frank Lloyd Wright referred to it as his “little gem,” the small house in Rockford he designed for Ken and Phyllis Laurent, the only house he designed for a person with a disability. The house, completely rehabbed by the Laurent House Foundation, opened to the public for tours in 2014. Jerry Heinzeroth, Foundation President, was kind enough to meet Skip and me at the Laurent House this summer for a tour of the home and to share the home’s history with us.

Shortly after Ken and Phyllis Laurent married in 1941, World War II broke out, and Ken enlisted in the Navy. During a tour of duty, Ken was experiencing painful problems with his back. He underwent surgery for a tumor on his spine, the surgery went awry, and Ken ended up a paraplegic, paralyzed from the waist down.

Don’t miss a Midwest Wanderer post. For a FREE subscription, enter your e-mail address in the Subscribe2 box to the left and click Subscribe.

While Ken was recuperating at Chicago’s Hines VA Hospital, Phyllis read an article in House Beautiful about the Pope House in Falls Church, Virginia, a Usonian house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. “Usonian” is the term given to the style of homes Wright designed for middle-income families. The term means “United States of North America.” Impressed with the design of the home, Phyllis shared the article with Ken, who wrote to Wright asking him to design a home that would accommodate his disability and at a price of no more than $20,000. At the time, Ken had no idea of Wright’s notoriety.

At 82 years of age, Wight took on the assignment. However, it was two years before the design was complete. Having thought it all out in his head, Wright put it on paper within two hours. A year later, in 1952, the house was completed, with much of the millwork done by local craftsmen. In 1960 an addition was put on the house, also Wright designed, that included a carport and dining room.

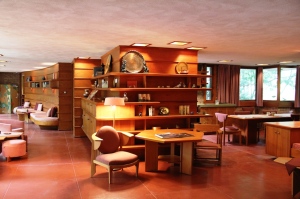

The house looks rather plain from the outside, but there’s no mistaken the Frank Lloyd Wright design, with its clean horizontal lines. As I entered the house, though, my jaw dropped. The open floor plan makes the house looks much larger than it looks from the outside. The design follows a solar hemicycle; if you look from one end of the house, you can see how the arcs continue to the other end.

The house looks rather plain from the outside, but there’s no mistaken the Frank Lloyd Wright design, with its clean horizontal lines. As I entered the house, though, my jaw dropped. The open floor plan makes the house looks much larger than it looks from the outside. The design follows a solar hemicycle; if you look from one end of the house, you can see how the arcs continue to the other end.

The 60-foot window wall at the back of the house is the longest in any Frank Lloyd Wright home. The window overlooks the patio that conforms to the same curves as the interior of the home.

To meet the budget needs of the homeowners, inexpensive but sturdy materials were used, like the Cherokee red concrete floor, coated with wax. Bug and disease resistant red tidewater cypress wood was used throughout the house. Chicago common brick was used on the home’s exterior.

The home was built with Ken’s eye level in mind as he was seated in his wheelchair, so everything sits a little lower, including the furniture, all original to the home and designed by Wright. In fact, the Laurent House includes the largest Frank Lloyd Wright collection in a single property.

Wright owned a large collection of Japanese block prints. When he designed the windows in the master bedroom, he said it was like giving the Laurents three Japanese prints that would change with every season.

Every aspect of the home was built to accommodate Ken’s accessibility, including a bathroom large enough to turn the wheelchair as needed and a desk for the office corner of the bedroom. The dining room table only had seven chairs, leaving a space for the wheelchair.

About $400,000 went into the restoration of the home, including restoring the woodwork and rewiring all of the electrical. The ceiling that was badly damaged by rain was completely redone and now includes a supplemental heating system should the original radiant heat that runs through iron pipe beneath the concrete floor ever go out.

About $400,000 went into the restoration of the home, including restoring the woodwork and rewiring all of the electrical. The ceiling that was badly damaged by rain was completely redone and now includes a supplemental heating system should the original radiant heat that runs through iron pipe beneath the concrete floor ever go out.

Many of the Laurents’ personal effects were left in Wright’s little gem, including a 108-year-old Schumann piano, made in Rockford. Like most Wright homes, nothing ever hung on the walls, as the walls were art in themselves.

The Laurent House is open for tours the first and last weekends (Saturday and Sunday) of every month, by reservation. Because there is no available parking on the property, tours begin at Midway Village, 6799 Guilford Road in Rockford, where you will board a shuttle bus and be brought to the Laurent House. Admission is $15 and best suited for children over eight years old. To make reservations or to learn more about the Laurent House, please visit the web site.

The Laurent House is open for tours the first and last weekends (Saturday and Sunday) of every month, by reservation. Because there is no available parking on the property, tours begin at Midway Village, 6799 Guilford Road in Rockford, where you will board a shuttle bus and be brought to the Laurent House. Admission is $15 and best suited for children over eight years old. To make reservations or to learn more about the Laurent House, please visit the web site.

Disclosure: Our visit to the Laurent House was hosted by the Rockford Area Convention and Visitors Bureau and the Laurent House Foundation. However, opinions expressed in this post are my own.

Thank you for reading Midwest Wanderer. Don’t miss a post. Enter your e-mail address below and click Subscribe to be notified whenever I publish another post. Subscription is FREE. After subscribing, be sure to click the link when you get the e-mail asking you to confirm. – Connie

Owl Prowl: Calling Owls in Wisconsin’s Wilderness

Our itinerary instructions said to meet at the North End Trailhead at 8 p.m. to call in barred owls. If it was October, there would have been an element of Halloween eeriness about it, driving down dark, silent North Wisconsin forested roads, meeting an owl caller who attracts birds of prey. My imagination could run wild with that. But it was July and still light as we made our way to the meeting place following maps and signs. The GPS wouldn’t do for this destination.

Don’t miss a Midwest Wanderer post. For a FREE subscription, enter your e-mail address in the Subscribe2 box to the left and click Subscribe.

Skip and I met Susan Thurn, a naturalist formerly with the nearby Cable Natural History Museum and expert barred owl caller, accompanied by Emily Stone, the museum’s current naturalist. A newlywed couple on their honeymoon were the other participants in the evening’s activity.

Before the calling began, Susan shared some interesting facts about barred owls:

- They can’t move their eyes in their eye sockets

- They have extra vertebrae in the neck and can turn their neck 270 degrees

- If they could read, they’d be able to read a newspaper from across a football field

- Human eyes would have to be the size of grapefruit to see as well

- Barred owls nest in tree cavities or in old nests of hawks or crows

- They breed once a year, in February or March

- Males weigh on average 1.5 pounds, and the females average 2 pounds.

- The weight is mostly feathers

- Wingspan is about 38 to 42 inches

Susan demonstrated how the soft, feathered edges of the owl’s wings dampen the sound made from flapping wings.

We also passed around an owl talon and an owl pellet. Owls eat small prey whole and then regurgitate non-digestible parts. The pellets are usually bones covered with fur.

We also passed around an owl talon and an owl pellet. Owls eat small prey whole and then regurgitate non-digestible parts. The pellets are usually bones covered with fur.

Although there are several kinds of owls that make the Wisconsin Northwoods their home, we would be calling only barred owls.

Although there are several kinds of owls that make the Wisconsin Northwoods their home, we would be calling only barred owls.

Susan has the sound of the barred owl down pat. She once used a machine that compared her call to the call of a barred owl, and it match almost perfectly. You can hear a barred owl sound (click to listen) on Learner.org’s online Owl Dictionary. It sounds kind of like “Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you all?”

We learned the sound together as a group and then stayed completely silent while Susan called an owl. She said they don’t always call back; it depends on how close by they are. When they do call back, they may actually come closer, to protect their territory, or move farther away, to leave another owl’s territory.

Silently we listened as Susan called, “Hoo hoo hoo hoooo, hoo hoo hoo hooo.” Silence, She called again. This time we heard an answer. “Hoo hoo hoo hoooo, hoo hoo hoo hoooo.” Susan called again, and we got another answer. This went on for a couple of minutes, each time the owl sounding farther away. Susan says she always lets the owl “win” by ending her calls before the owl does.

Silently we listened as Susan called, “Hoo hoo hoo hoooo, hoo hoo hoo hooo.” Silence, She called again. This time we heard an answer. “Hoo hoo hoo hoooo, hoo hoo hoo hoooo.” Susan called again, and we got another answer. This went on for a couple of minutes, each time the owl sounding farther away. Susan says she always lets the owl “win” by ending her calls before the owl does.

By the time we left, night was falling. Even though it was nowhere near autumn, a bit of Halloween eeriness was in the air in the dark forest that was once again completely silent.

Owl Prowls, held about four times each year, are one of many events sponsored by the Cable Natural History Museum, Cable, Wisconsin. Donations are welcome from event attendees.

Disclosure: Our trip to northern Wisconsin was hosted by the Wisconsin Department of Tourism, but any opinions expressed in this post are my own.

Thank you for reading Midwest Wanderer. Don’t miss a post. Enter your e-mail address below and click Subscribe to be notified whenever I publish another post. Subscription is FREE. After subscribing, be sure to click the link when you get the e-mail asking you to confirm. – Connie

Exploring Omaha’s Old Market District

I love exploring revitalized historic districts like Omaha’s Old Market District. 1880s brick buildings line the district’s cobblestone streets. Unique shops, art galleries and interesting pubs and restaurants fill those buildings. Omaha resident and fellow travel blogger Lisa Trudell, half of The Walking Tourists, introduced my husband and me to the area. Read more

Relive the Fifties at Bristol 45 Diner

No matter your age, it’s always fun to step back to the 1950s, the era of diners with soda fountains and juke boxes that played your favorite rock-and-roll songs. Bristol 45 Diner in Bristol, Wisconsin, lets you do exactly that. We stopped in for breakfast during our July trip to the Kenosha area and were impressed with both the fun ‘50s atmosphere and the delicious food we were served. Read more

Shop the South Bend Farmers Market Year Round

By October most farmers markets are fizzling out for the season. Once the pumpkins and squash are gone, the fall breeze turns to winter wind, and the vendors leave for the winter. Not so in South Bend, where the market is open year-round. Read more